TL;DR - No Need to Panic

Your Screenly account is secure. We investigated a reported data leak and confirmed it did NOT originate from our systems. The leaked data came from malware-infected devices and password reuse from other breached services. Only 228 accounts (less than 1% of users) were affected, and we’ve already reset their passwords as a precaution. We’re also implementing Magic Links this week to eliminate passwords entirely and make your account even more secure.

What happened?

Yesterday (Sunday), we received an email through our Bug Bounty program that should make any CEO or CTO skip a beat: a report that a large amount of our users’ data had been leaked. What’s worse, it had been posted on a public forum (Leak Radar). The security reporter was helpful enough to attach a dump of what had been posted.

Upon inspecting the data in a clean room environment (just in case it was compromised), we discovered that the leak included almost 1,400 user accounts, complete with usernames and passwords in plain text.

This is where you start sweating.

A leak of such size usually means that the backend was compromised. We immediately started thinking about possible attack vectors that could lead to a leak of such magnitude.

As we dove into the data, it became clear that this was a “dirty” data dump, meaning that much of the data didn’t even make sense. We started filtering out data that didn’t make sense (e.g., usernames that didn’t match our structure), and then we de-duplicated this list.

We were now down to ~300 user accounts, which was less than 1% of our users. Still bad, but this changed the equation from “definitely something on our end” to it becoming plausible that these were either datasets with reused passwords and/or from compromised end-user devices (spoiler: it was).

The next step was to correlate the reported usernames with our actual data to see if they were even real accounts. At this point, we had already spot-checked and confirmed that at least two of the accounts existed in our system.

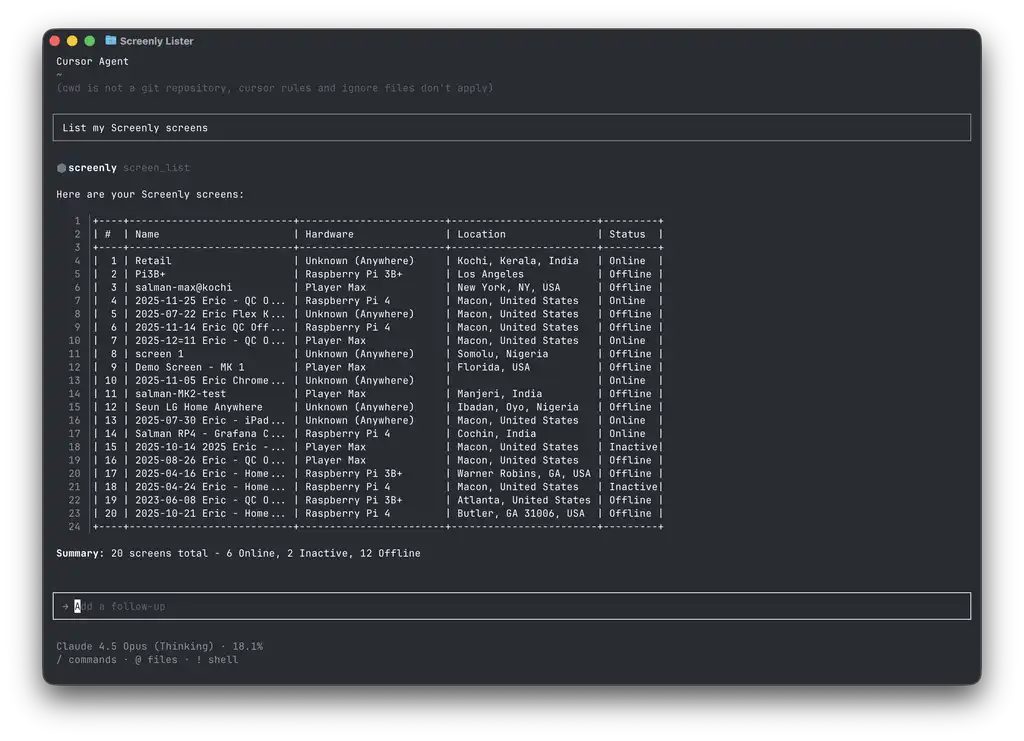

After writing some custom tooling, we were able to find the following:

- 228 of the ~300 accounts actually existed in our system

- 41 out of the 228 accounts had activity in the last year

- 5 of the 41 accounts were actual paying customers

The first thing we did at this point was to reset the passwords on all affected user accounts to minimize the blast radius of the leak (regardless of how it came to be). Note that this was within about three hours after the report — on a Sunday night. This is where I must give a massive shout-out to our CTO, who was leading this effort in the middle of the night in his time zone.

At this point, we had done the most pressing damage control to mitigate the blast radius of the leak. We could continue in the morning with the rest of the team.

While we started to reach out to the affected users, we simultaneously started looking at both the audit logs for these users and the patterns around them. For instance, were they all created or accessed around the same time? No immediate pattern emerged. Some were several years old, others were somewhat new. The vast majority of the accounts, however, hadn’t been accessed for a long time.

The plot thickens.

After investigating our internal systems, including access logs, we became confident that there was no breach in our system. If the breach was not on our end, where did the data for this leak come from?

Enter Have I Been Pwned. For those not familiar, Have I Been Pwned is an open database that allows you to monitor if you have been part of a data leak. They also have a great API available. Was there a leak that correlated with all these accounts? Turns out there was.

The vast majority of the 228 accounts existed in one of three leaks:

- Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data Breach

- Data Troll Stealer Logs Data Breach

- ALIEN TXTBASE Stealer Logs Data Breach

What’s important to note here is that all these sources are “stealer logs”, meaning that most of them appear to have been captured directly from compromised desktops. These are malware-infected machines where credentials were stolen from browsers.

With all this data, we became confident in concluding that this was not a breach on our end, but rather a combination of compromised end devices and reused passwords.

This is an attack vector that is difficult to protect against, but we believe we can better protect our users from this type of attack going forward.

What we are doing next

Even though this leak didn’t appear to have originated from an issue on our end, we still wanted to do better. We have supported SSO and Multi Factor Authentication (MFA) for many years. This certainly helps improve our overall security posture, but many users still choose not to use it. For instance, none of the users in the leak had MFA turned on.

Also, we can’t prevent users from reusing passwords from other services, which exposes their Screenly account even if we have the best security posture in the world.

So how can we make our customers more secure without adding more friction? Many services are moving to passkeys, a great technology we’re fans of, but we’re not convinced it would have changed anything in this scenario.

Instead, we decided to implement Magic Links and get away from passwords altogether. This is a well-established concept by now that is widely used. The way it works is very simple. Instead of creating a username and password, when you log in with your username (e.g., your email address), we will send you a Magic Link. When you click on this link, you will automatically be logged in. It’s straightforward and secure.

And the best part is that even if we were to be affected by a leak in the future, it would not be exploitable as we don’t even have passwords on file.

Work is underway on Magic Links, and we expect this feature to go live this week.

What can I do to improve my security?

When we looked through the data set of leaked users, the vast majority of them appeared to be small businesses. If we contacted you, we would advise you to do an audit of all your devices as well as your overall security posture. After all, there was (or at least had been) malware that infected at least one of your devices. This is serious. Yes, your Screenly account is safe, but there is a strong probability that many of your other online services were also impacted (but you just might not know it yet).

So what should you do?

- First, sign up to Have I Been Pwned. It’s a reputable service that will monitor your emails for past and future breaches and notify you if you have been affected. Best of all, it is free!

- Enable Two Factor Authentication (2FA) / Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) on all your accounts. Yes, it creates a bit more friction on a day-to-day basis, but it will save you from issues like this in the future. As mentioned in the post, none of the affected Screenly users had 2FA enabled, despite it being a free option. Some password managers (see below) can also handle 2FA, which minimizes the friction further.

- Make sure your devices are still supported and receive security updates. You can use endoflife.date to check that your desktop and mobile devices are still receiving updates.

- Install endpoint protection on your devices. Speak to your Managed Service Provider (MSP) and see what they recommend.

- Last, but not least, never re-use passwords. Use a password manager (we use 1Password at Screenly), but there are a lot of both free and paid options available. The tool you choose matters less than adopting a habit of never reusing passwords.

By following these security practices, you’ll significantly reduce your risk and make any future data leaks much less damaging to your accounts.

Timeline

- 2025-11-09 (Sunday) 19:21 UTC: Bug Bounty report received about customer credentials being leaked on a public forum

- 2025-11-09 (Sunday) 21:00 UTC: Investigation began in clean room environment; confirmed that a subset of reported users were legitimate accounts in our system

- 2025-11-09 (Sunday) 23:22 UTC: All affected users’ passwords were reset as a precautionary measure to neutralize the leaked data

- 2025-11-10 (Monday) 08:30 UTC: Investigation continued with full team to analyze patterns and correlate with external breach databases

- 2025-11-10 (Monday) 16:30 UTC: Investigation concluded that the leak originated from stealer logs on infected devices and password reuse, not from our systems

- 2025-11-10 (Monday) 18:00 UTC: Planning began for migration to Magic Links to eliminate password-based vulnerabilities

- 2025-11-10 (Monday) 22:30 UTC: All affected users were individually contacted by our Customer Success team with details and next steps

Finally, a big shout-out to Nick Selby from epsd for advisory on our incident response plan.